So you’re thinking about your next car and wondering whether buying an electric car (also known as ‘EV’) makes sense? You’re not alone. According to the latest survey conducted by the Electric Vehicle Council, 54% of people would consider buying an EV for their next car. We believe EVs are the future and will eventually make sense for everyone.

We also know they can be confusing so we’ve put together this beginner’s guide on EVs. We’ll bust some myths, look at some examples and outline the key things you need to know before going electric. Feel free to check out our Electric Car Dictionary to familiarise yourself with all the key terms in the EV 🌏.

Pros & Cons of Buying an EV

We’ve talked to hundreds of owners and reviewed dozens of surveys and reports; the key recurring reasons for buying (and not buying) are almost always the same. So we’ve summarised them below for you:

We are confident the reasons for going electric are factual and will benefit everyone, whereas the reasons for not buying do not always hold true and very much depend on your individual circumstances. Read this guide, use our tools, subscribe to our newsletter (bottom of this page) and you’ll have a much better idea of where you stand.

How Are EVs Different?

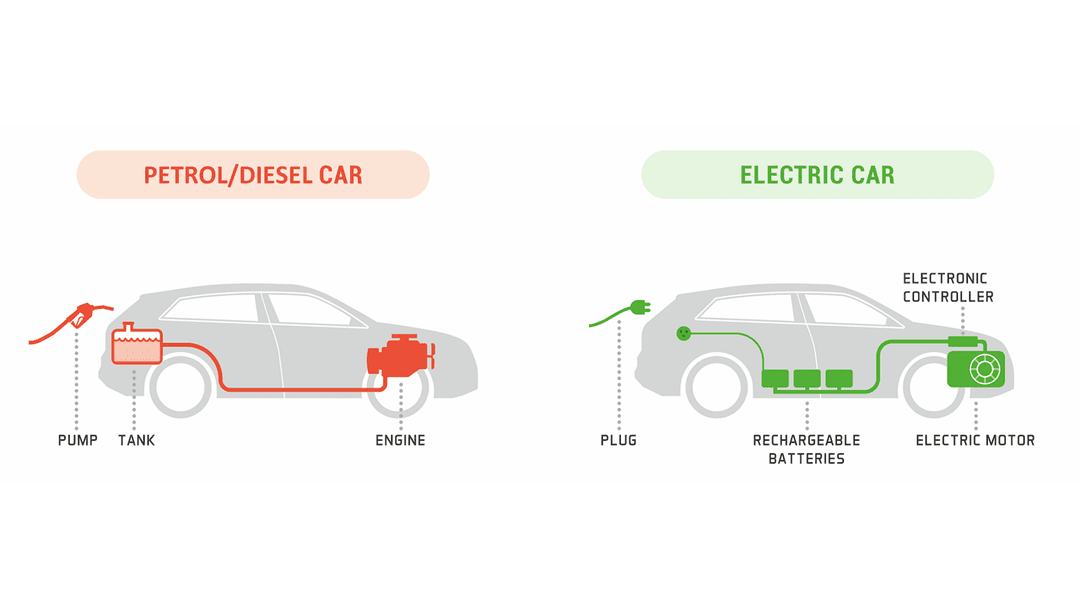

From the outside, electric and petrol/diesel (also known as ‘ICE’) cars look more or less the same, under the bonnet however is where they are different. How so? In an EV, energy comes from the batteries and is sent to an electric motor/s. In an ICE car, energy comes from petrol in the fuel tank and is sent to an engine. Hybrids and plug-in hybrids combine elements of both but for the purposes of this guide, we’ll just focus on fully-electric and petrol cars.

The True Cost of Owning an EV

Cost of Batteries

The biggest hurdle when it comes to the adoption of EVs is the higher upfront cost compared to their ICE equivalents. Why are they more expensive? Because batteries, which comprise up to a third of the cost of an EV, are still expensive. The good news is that battery prices are decreasing rapidly and the upfront cost of an EV and an ICE is expected to be roughly the same by 2025.

Cost to Run

Today, however, electric vehicles cost more. Depending on the vehicle, up to 40% more than an ‘equivalent’ ICE vehicle.

The upfront cost, however, is only a part of the total cost equation. Over the life of a car, the upfront cost comprises 45% of the total cost of ownership (TCO). To know the true cost of car ownership you need to consider the ongoing running costs (fuel, service, maintenance) as well.

The cost to run an electric vs petrol are on average much lower (refer chart 1.4 below). Increasingly, we are finding the overall ownership costs (TCO) of EVs is lower than ICE cars. Firstly, this means that over the life of the vehicle, an EV will cost less to own. Secondly, the additional upfront cost for the EV will be 'repaid' from the savings from lower running costs. Yes, despite their higher upfront cost, EVs can be cheaper to own and operate than their ICE equivalents in the majority of cases.

The two key factors driving an EV's lower operating costs are lower fuel and maintenance (this is discussed in more detail in the next section).

Cost per 100 km

For the same distance driven, EVs are cheaper to charge than ICE cars are to fill up. For example, at today's prices (petrol $2/litre and electricity $0.25/kWh), it costs c. 80% less to cover the same distance by an EV.

Due to their mechanical simplicity, EVs have lower ongoing maintenance and service requirements and costs (discussed below).

Operating cost savings from EV ownership is positively correlated with distance driven.

Case Study: Total Cost of Ownership

To illustrate the effect of this relationship, we look at two drivers - Jim and Kim, who are contemplating the financial case for an EV. They are both interested in the MG ZS EV, one of the most affordable EVs in the market as of 2021. Its petrol equivalent, the MG ZST, shares the same platform but is powered by a 1.3 litre petrol-turbo engine.

Jim drives roughly the Australian average distance of 36.4 km per day (12,740 km per year). In contrast, Kim drives double that, 73.8 km per day (25,480 km per year).

Annual operating savings = distance driven x operating costs

Because Kim covers more distance, he'll be able to realise higher annual savings relative to Jim and as a result, have a faster payback on the additional cost of the EV (refer to the table below).

The ‘financial’ case for EVs is not black and white. It will vary depending on the vehicle and your personal circumstances. We recommend using our cost of ownership calculator to get a better indicator of your personal circumstances.

If upfront cost is front of mind, the next few years is expected to be pivotal, with a raft of models targeting in the $30,000 to $45,000 (pre-incentives) expected to be released in 2022 and 2023.

Servicing and Maintenance for EVs

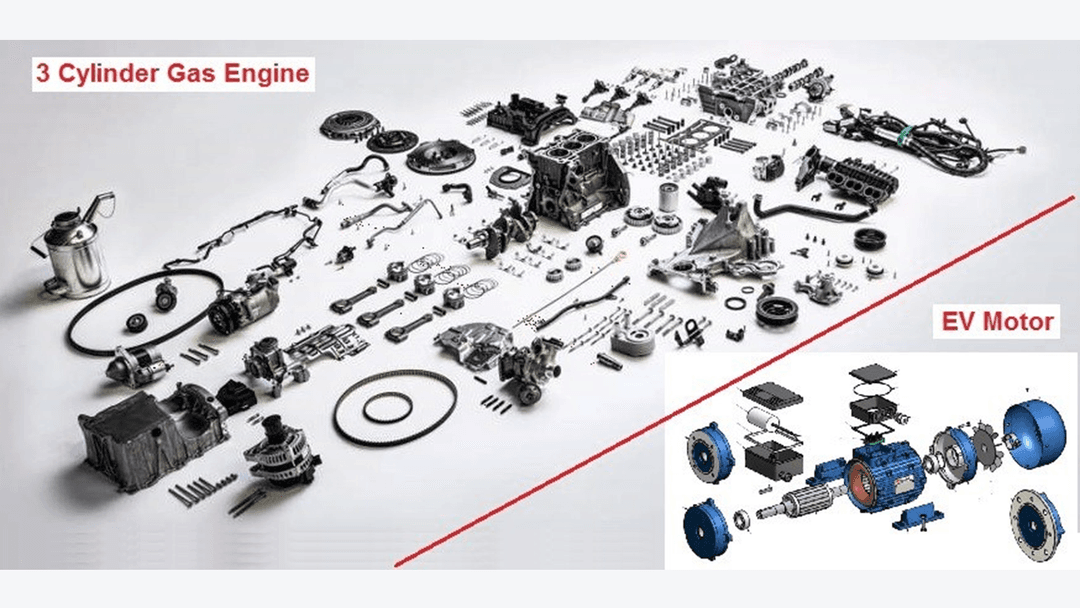

EVs are by design much simpler machines. They comprise fewer moving parts (200 vs. 2000) compared to an ICE car. This means less wear and tear and consequently less servicing and maintenance needs.

Servicing and maintenance costs are lower as you’ll forgo the need to spend on common ICE consumables (spark plugs, valves, fuel tank, exhaust systems, clutches, drive belts, hoses, etc).

Servicing intervals for EVs are generally longer (although this depends on the manufacturer). Brakes may last longer due to regenerative braking. For example, the electric MG has 24-month servicing intervals, whereas the petrol equivalent is 12-months. The Tesla Model 3 does not have fixed service intervals at all.

Over the lifetime of an EV you can expect service and maintenance costs to be in the range of 10% to 30% lower based on the 2021 edition of RACV's annual car running cost report.

Is EV Range Anxiety Real?

‘Range anxiety’ is one of the biggest fears (and misconceptions) people tend to have about EVs.

Yes, on average, EVs have a shorter range than ICE cars. People also tend to overestimate the range they need to meet their day-to-day driving needs. Contrary to common belief, modern EVs have a good range (200km to 600km), enough to meet the daily driving needs of most people. Even longer trips, like the annual family trip up or down the coast, can be comfortably completed in most EVs so long as there are public fast charging options along the way.

When deciding on the range you actually need for an EV, the most important considerations are your driving needs and your charging options (discussed in the next section).

At zecar we believe in choosing the right vehicle for your needs. Bigger is not always better. The longer the range, the bigger the battery and the higher the cost (financially and environmentally). Our EV matching tool takes a holistic view of your budget, driving needs, and charging options to determine which EV best meets your needs.

EV Charging Options and Practicality

The lack of EV charging infrastructure is one of the major concerns many people have with EVs. Similarly to range, your reliance on public EV charging depends on your individual circumstances.

For example, this is likely to be minimal for those with access to on-site charging at home or work. Many EV owners who charge their car at home say it is easy and convenient to charge while idle in their driveway/garage. Time is thus saved not having to visit a petrol station.

If you have no or limited access to on-site private charging, like many apartment building residents, you may find EV ownership impractical due to the need to rely on public charging. Today, there are fewer public charging stations than petrol stations. The good news is, the Australian Government has recognised the need for increased EV charging infrastructure. It recently announced a $250m investment towards EV and low emissions vehicle charging infrastructure.

Charger types

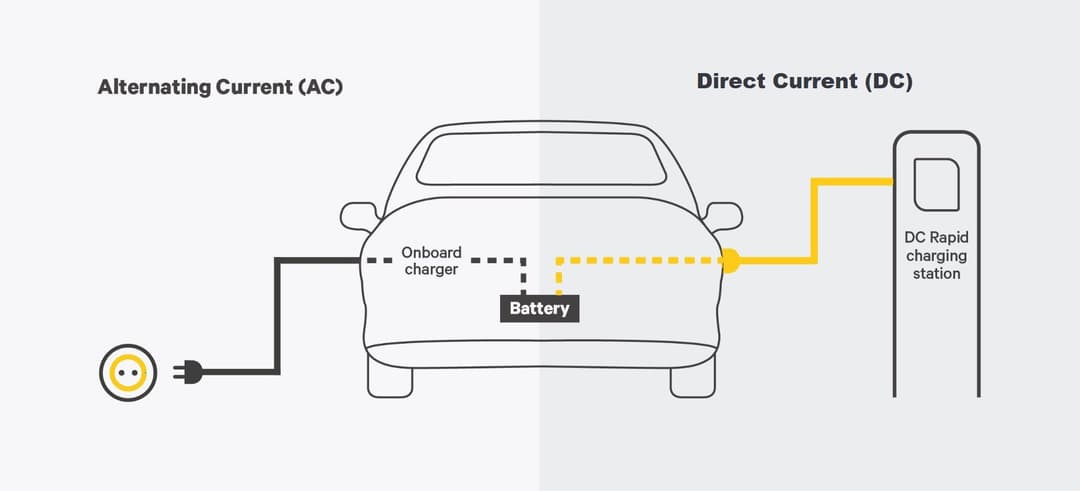

One of the more confusing things EV owners need to get their heads around is the plethora of EV charging options. AC/DC, level 1/2/3, fast/slow - what does it all mean? We've summarised the EV charging basics you need to know below.

The use of Alternating Current (AC) or Direct Current (DC) will determine the type of charging option being used. When an EV is being charged, AC electricity from the grid is converted to DC so it can be used by the car battery. This is done by a ‘convertor’ which is located in the car or in the charger.

Charging times

Fully charging an EV will generally take anywhere from 15 minutes to over a day, depending on the size of the battery and the charger being used. This is considerably longer than refueling an ICE car and one of the major potential impracticalities of EV ownership.

The good news is that chargers are getting faster with 350kW chargers now being rolled out - which can provide 100km of range in 5 minutes. Note: Only some EVs like the Hyundai Ioniq 5 have this super-fast charging capability. You can check out the charging capabilities of all EVs in our database.

To give you a better idea of how long it generally takes, we’ve outlined the common charger types and typical speeds at which they can provide range for your EV.

Case study: The ‘Convenience' factor

The need to charge an EV does not always make it more impractical to own. To illustrate how ‘convenience’ can vary with EV ownership we compare three drivers with similar driving profiles but different EV charging options.

1. Jane - Average distance, Smart home charging

Jane drives to work, covering an average distance of 36km every day. She parks her EV in a garage and charges it overnight.

For the daily distance she drives, it would only take 1.4 hours using a standard power outlet or 30 minutes using a level 2 charger. Level 2 chargers provide faster charging and are often equipped with 'smart' functions, like ensuring your car charges when your energy tariff is off-peak.

EV ownership works out to be convenient for Jane as she saves several hours per year by not visiting a petrol station. The only time she would need to use a fast charger is on longer trips outside of the city (300km+).

2. James - Average distance, relies on public EV charging

James lives in an apartment and does not have access to on-site EV charging. Instead, he relies on public EV charging.

Fortunately for James, there are three 50 kW fast DC chargers at his local shopping centre. He is able to meet his charging needs via a weekly 35-minute session which gives him 250km of range. This equates to an extra 30 hours per year charging compared to re-fuelling at petrol stations. This is not time wasted as James does his weekly grocery shopping while his car is being charged.

Overall, EV ownership is not any more inconvenient for James.

3. Peter - Longer distance, relies on public EV charging

Peter, like James, does not have an on-site charging option and has to rely on public chargers. He drives a considerable amount (100 km) per day and his budget limits his options to lower range vehicles.

Due to the significant distance he drives, he will need to spend at least 2.5 hours per week at public charging stations.

EV ownership is impractical for Peter. He does not have the time to accommodate the additional time required to charge an EV. An EV is unlikely to be a good option for Peter at this point in time.

The case study highlights the practicalities of EV ownership vary widely and depend on your individual circumstances. The nascent stage of battery and charging technology and the small footprint of public charging present will challenges for some in the near term.

As public EV charging infrastructure becomes more widely available and more chargers are installed at apartment buildings, along with technological improvements, it’s going to be increasingly difficult to ignore the case for going electric.

To find out what public chargers are near you, you can visit the Plugshare website.

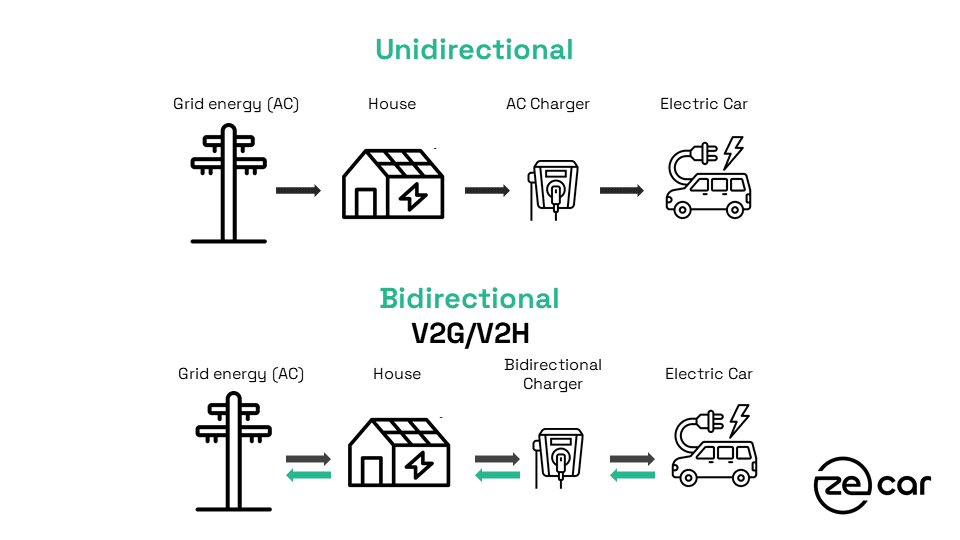

Bidirectional charging (V2G, V2H, V2L)

It is now becoming more common for EVs to also feature bidirectional charging capability. charging’ that occurs two ways (back and forth).

Energy will flow from the grid to the car or it can be sent back to the grid or power other devices.

Like a powerbank used to charge your electronic devices, your car can be used in the same way. In the case of EVs, the ‘devices’ are much larger – they could be a barbeque (V2L), your house (V2H) or the electricity grid (V2G). You can read more about this in our comprehensive guide "Watt is bidirectional charging, V2G, V2H, V2L?"

Batteries - do they last?

Rounding out the top 3 topics of EV myths are the concerns and misconceptions around batteries, particularly in relation to their useful life (or degradation).

The batteries in EVs, like in your phone, degrade with use over time. Whereas the ‘wear and tear’ for ICE cars relates to the engine, fuel, and transmission systems. In the case of EVs, it primarily relates to the degradation of the battery.

We won’t go into too much detail here on battery degradation as the market for used EVs is still very limited; however, we’ve summarised the key things to know below. Battery technology is constantly improving across key areas such as density and cycle life.

EV Driving Experience

EVs provide a different driving experience and for most people, it is a superior one. It's so good that according to this survey 9/10 people would not switch back to a petrol car after having owned an EV.

If your prerequisite in a car is the sound of a roaring V8, then maybe EVs might not be for you.

There are, however, many good reasons why people prefer the electric driving experience and we’ve summarised them below.

Government Grants and Incentives for EVs

If there is any country in the world where EV ownership makes the most sense, it would be Australia.

We have some of the cleanest and cheapest energy sources (the sun) to charge EVs and a large proportion, 86%, of our population is located in urban areas. Urban driving provides better range and efficiency for EVs.

Despite this, we have some of the lowest levels of EV uptake in the developed world. The main reason for this is, until recently, is the absence of government financial support.

The Australian Government is one of few in the developed world, who have not and do not provide any financial incentive for EV ownership (outside of modest lower luxury car tax payable).

There is good news. 2021 saw several state governments roll out a raft of financial and other incentives to encourage EV ownership. The introduction of incentives saw record growth in EV uptake in 2021.

Our guide to Australian EV incentives provides more details on the type of incentives each state has and when they take effect. If you're ready to buy, use our EV incentive calculator to find out what and how much you might be eligible for based on the car of your choice.

Are EVs Better for the Environment?

EVs are often labeled as zero-emissions transport because no carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are produced while the car is being driven. This is a misleading label for a few reasons.

Firstly, the manufacture of electric vehicles has a higher embodied carbon footprint than ICE vehicles, mainly due to the manufacture of the battery. Think of this as the upfront environmental cost.

Secondly, if your EV is charged from the grid, emissions will be emitted. The Australian grid is still predominantly powered by fossil fuels (coal and gas). Think of this as the ongoing environmental cost.

If an EV is going to have a net positive impact relative to an ICE car, it must have a lower total environmental cost (TEC). The emissions savings over the life of its operation needs to be greater than the higher upfront environmental cost.

Total Environmental Cost (TEC) = Upfront Environmental Cost of Manufacturing + Ongoing Environmental Cost of Operations.

As an EV owner, you can positively contribute to sustainable transport by charging your car via renewable energy sources. If you have your own solar system this would mean charging it during the day when the sun is shining. The environmental case for charging from the grid is improving by the day as record levels of renewable energy generation capacity continue to be added. This results in the mix of energy produced having a lower carbon footprint, which incidentally makes the operation of your EV cleaner.

About the author

Stay up to date with the latest EV news

- Get the latest news and update

- New EV model releases

- Get money savings-deal