Electric vehicle sales are rapidly growing in Australia, though it still remains a small slice on our roads.

Like many new and shiny things, there’s a lot of scepticism, hesitancy and misconceptions around owning battery-electric cars in lieu of internal combustion engine vehicles (petrol and diesel) – which we’ve been driving for more than a century.

In this three-part series, we definitively mythbust to ‘clear the air’ surrounding EVs. Here, we focus on the concerns around EV driving range, charging, and batteries. Also check out our other mythbusters here:

#1. “There aren’t enough EV chargers in Australia.”

False. While Australia has less public EV charging stations than other more progressive continents like the EU and USA, it is rapidly expanding. However, public charging infrastructure shouldn’t be a major concern as most EVs should be charged at home overnight, anyway; it’s more convenient and cost efficient – given Australia has one of the highest home solar panel installations per capita in the world.

According to Plugshare, there are currently 361 AC and DC public charging stations across Australia from major providers like Chargefox, Evie Networks and Jolt to independent local cafes and shopping centres.

Chargefox currently offers the widest charging network in the country, with more than 1400 plugs at around 260 locations. The Australian-born company allows EV owners to travel along the coast from Perth to Port Douglas using slower 22kW AC to ultra-rapid 350kW DC chargers thanks to investments by state Australian Motoring Services (NRMA, RACV, RACQ, RAA, RAC, and RACT), the Federal Government’s Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), JET Charge, and more. Notably, Chargefox mostly uses Level 3 DC stations from Tritium, a Brisbane-based global EV charging manufacturer.

But, the easiest way to top-up an EV is at your own home. Provided you have access to a power outlet in your garage or driveway, you can use the included three-prong cable to Level 1 ‘trickle charge’ at 2 to 3kW (15km per hour) overnight. If that’s too slow for your daily driving needs, investing in a Level 2 AC wallbox charger at 7kW to 22kW (40km to 120km per hour) will enable owners to conveniently charge overnight to a near-full battery – without needing to stop at a fast DC public charger (in lieu of gas stations).

Other than charging during the cheapest overnight electricity tariff, if you have a solar panel or home battery storage system, then ‘refuelling’ your EV could almost be free using energy generated from the sun.

#2. “Charging an EV is too slow.”

False. Electric cars sold today typically take around one hour to charge to 80 per cent (recommended to preserve battery health) on a fast DC charging stall. You can find out how long each EV takes in our database. Though, since public chargers are often located near point-of-interest locations like shopping centres, supermarkets and parks, owners can explore or do some errands while the EV’s juicing-up. Alternatively, owners can stay in the vehicle and work, stream, play or relax – while keeping the climate control on using power from the charger itself.

EV charging speeds are rapidly advancing, too. The Renault Megane E-Tech crossover is capable of up to 130kW DC fast charging rates, adding a claimed 300km of range in 30 minutes. Meanwhile, some carmakers are adopting 800-volt charging technology, which can juice up cars like the sleek Kia EV6 from 10 to 80 per cent in a claimed 18 minutes at up to 233kW speeds on a compatible DC charger. This is particularly useful when on long-distance drives.

Keep in mind, there’s no rush to fill up your EV at home. Using a standard three-prong socket or installed AC wallbox will often provide you enough battery juice for the next day by charging during the cheapest electricity rates overnight when the EV isn’t in use.

Additionally, as more models feature strong regenerative braking, slicker aerodynamic designs and more efficient electric motors will mean charging will become less frequent in the future thanks to eking out more range.

#3. “EVs can’t drive very far.”

False. EVs currently provide an average of 400km driving range as at publication. However, just like how large a fuel tank is on a conventional combustion-powered vehicle, not everyone needs the largest battery pack for the longest range.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australians typically drive around 35km per day in a passenger car. Add your typical commute to work, school, shops and the odd long distance trip into our EV match calculator tool to work out which pure-electric models are suited to your needs.

For some drivers, the Mini Cooper Electric city car with a small 28.9kWh (usable) battery pack, good for a claimed 185km on the strict WLTP testing cycle might be enough. Yet, others may prefer the Cupra Born hatch with the long range 77kWh (usable) pack, able to drive a claimed 450km (WLTP). As EVs develop, carmakers are aiming to sell models with 1000km of range soon.

It all depends on your situation and driving needs. Don’t forget that, if you have convenient access to a powerpoint at home, you can ‘set and forget’ by recharging every night anyway, so you will rarely have so-called ‘range anxiety’.

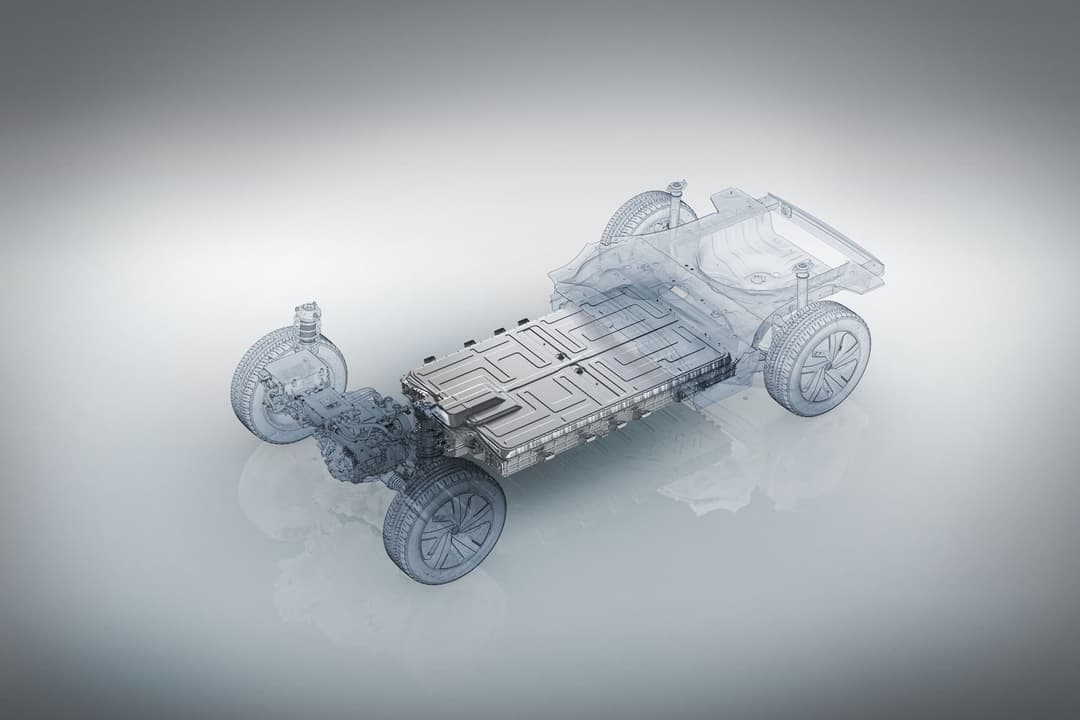

#4. “EV batteries won’t last long.”

False. All batteries’ health will naturally degrade over time, though studies have proven EV batteries degrade very little due to provisions like active thermal management systems and ‘top buffers’.

Online creator Bjørn Nyland tested his 2013 Tesla Model S P85 liftback, revealing its liquid-cooled battery only degraded 11 per cent (8.1kWh loss) or around 100km less driving range than new after seven-years and 260,000km driven.

Carmakers also employ battery ‘top buffers’, which are small reserves that automatically activate when degradation appears over time; this alleviates the impact of reduced range for owners. This is why there’s a gross (total) and net (usable) figure quoted for EV battery capacities.

A variety of factors affect battery health, including how often you drive, operating temperatures, charging cycles, frequency of DC fast charging, and more. Car brands back its electric models with a dedicated high-voltage battery warranty to cover any defects and abnormal degradation effects beyond what is promised. Currently, the industry warranty standard extends eight-years/160,000km, with carmakers usually promising its EVs will hold 80 per cent of its original capacity during that warranty period.

Additionally, lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries are proliferating in more models, which lasts longer than the more common nickel-manganese-colbalt (NMC) chemistry. According to battery manufacturer Green Cubes Technology, LFP batteries deliver at least 2500 to 3000 full charge/discharge cycles before degrading 20 per cent of its original capacity, as opposed to NMC batteries which only deliver 500 to 1000 full charge/discharge cycles. As a result, LFP batteries offer four times more cycle life than typical NMC packs according to the company.

Automakers are also delivering slower DC charging speeds in order to preserve the health of the battery by generating less heat. For instance, the bespoke Build Your Dreams (BYD) Atto 3 electric SUV only charges at a maximum 80kW rate to claim its LFP battery will suffer from 'very little' degradation over a million kilometres of driving. Meanwhile, the Volkswagen Group's ground-up EVs like the Cupra Born hatchback only charges at a claimed 125kW peak on a DC fast charger.

#5. “EV batteries are dangerous.”

False. While there have been numerous reported EV battery recalls and fires, it is natural for lithium-ion batteries to pose a fire risk when it has been improperly manufactured, operating in extreme temperatures, or is damaged.

Liquid electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries are flammable, burn hotter, faster and are harder to extinguish – exacerbated by thermal runaway, which further increases temperatures and gases.

However, manufacturers implement safeguards like active liquid-cooling, battery, charging and motor management software, thick metal reinforced battery casings, and separate firewalls for battery cells to prevent punctures and chemical leakage.

Today, LFP batteries emerging in more affordable EVs also contain a safer cathode material than NMC packs, providing the "best thermal and chemical stability", according to Green Cubes. BYD's LFP ‘Blade Battery’ is claimed to be significantly more durable and safer than conventional packs, while future solid-state batteries use a solid electrolyte that doesn't leak organic chemicals.

In the event of a crash, EVs intelligently disconnect from all electronics and the high-voltage battery to prevent a short circuit from chemical leakage. Most states in Australia now mandate small blue EV stickers on all licence plates for electric vehicles, including hybrids and plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), to alert emergency services to manage a situation differently due to the presence of a high-voltage battery.

In contrast, conventional petrol and diesel vehicles actually pose a higher safety risk than battery-electric vehicles. Research by AutoinsuranceEZ reveals the likelihood of vehicle fires are:

- Battery-electric – 0.03 per cent

- Internal combustion engine – 1.5 per cent

- Hybrid and PHEV – 3.4 per cent

Internal combustion engines, as the name suggests, constantly ignite fuel and air via a complex system of cylinders, pistons, crankshafts and gears to drive the vehicle. They also house highly combustible unleaded fuel, where special foam and chemicals are required to douse a fire.

Like all vehicles, electric cars undergo extensive durability testing to ensure the vehicle and battery are protected from extreme weather conditions and elements.

Figures by Danny Thai

About the author

Stay up to date with the latest EV news

- Get the latest news and update

- New EV model releases

- Get money savings-deal